What is the history of Ethernet indeed? How and who had came up with such a visionary idea that later changed our world?

In 1973, the employees of Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center including Bob Metcalfe and Dave Boggs, were like many young developers at startups at Silicon Valley nowadays.

Image 1: Bob Metcalfe and David Boggs

Metcalfe recalled that he and his coworkers wore T-shirts, Birkenstocks and blue jeans and sported beards when they went to work during its peak 40 years ago. Metcalfe was 27 at the time, sported a red beard and they worked at a cluster of low-slung, modern buildings amid suburban fields.

When the employees went over to PARC’s conference room for a meeting, they lounged around in beanbags, the only seating available. The relaxed setting did however disguise an extreme environment where working around the clock was common.

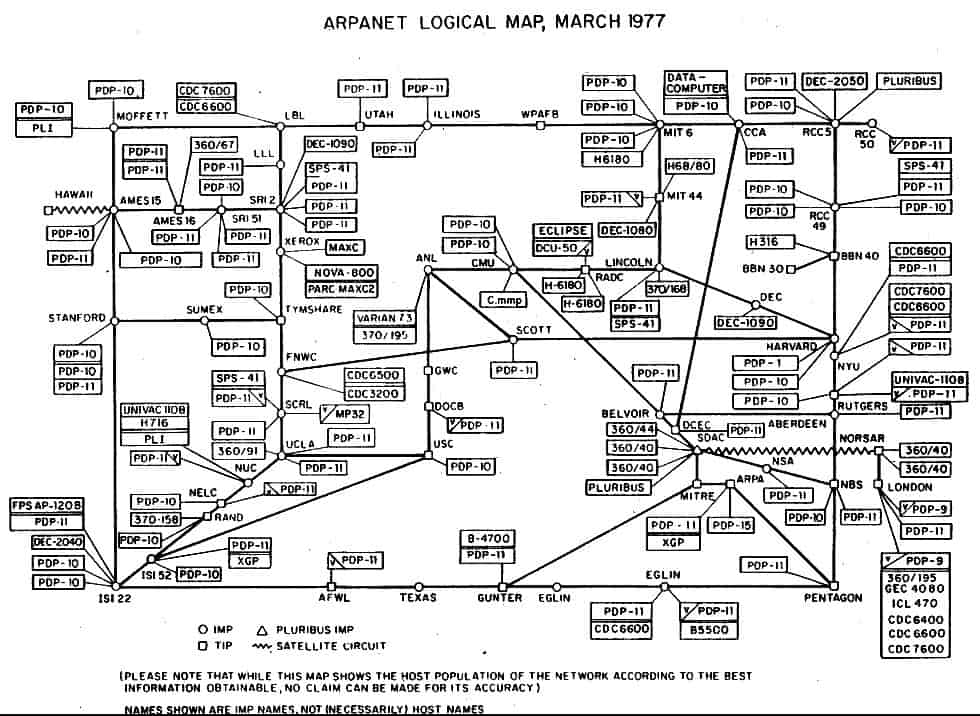

Soon after Metcalfe arrived at PARC in mid-1972, he set up a connection to the internet. Employees at PARC and other organizations at the time could link to other computers over extreme distances using something called Arpanet.

Figure 2: Arpanet logical map around 1977

The Web, Netflix and Facebook were however still years away as the modern Internet requires a much faster network. PARC was inventing laser printers that needed a network fast enough to send memos to it.

Just to mention also that the first mass-market Ethernet network printer, the HP LaserJet IIISi, debuted in March 1991. Priced at $5,495, it featured a high-speed, 17 ppm engine, 5MB of memory, 300-dpi output, Image REt and such paper handling features as job stacking and optional duplex printing.

Image 3: First Ethernet Network Printer

This was the beginning of faster networks, while emails, images, voice, music and video all followed later.

Metcalfe worked with Boggs, a graduate student at Stanford at the time, to build a faster network, using the packet concept of Arpanet as a basis and getting help from many other employees at PARC.

Metcalfe sent a memo to his team on 22 May 1973 describing the architecture they had developed. It was named “The Ether Network”, a name that is still around today with new generations of researchers exploring how the technology can carry 1 terabit per second.

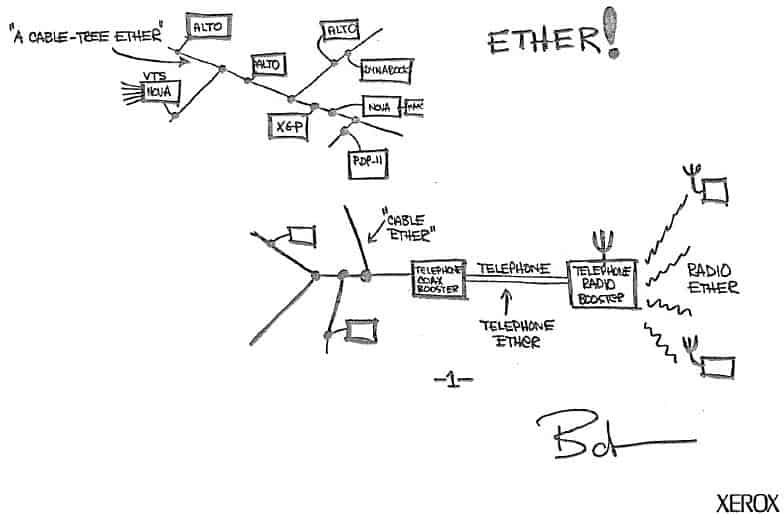

Image 4: Original sketch of The Ether Network

Metcalfe, along with others that were around at the dawn of Ethernet, marked its 40th anniversary in 2013 at the Ethernet Innovation Summit that was held at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.

Ethernet was not discovered accidentally. Metcalfe worked on Arpanet for 2 years, after which he was hired to develop a network that would link new computers at PARC. Alan Kay, a visionary at PARC had invented the Alto, which consisted of a computer for each desktop.

Metcalfe explained that this created a new problem – how to link a company full of personal computers.

The LANs available in those days had severe limitations. PARC used one of those to link Data General Nova minicomputers used by the company. It was known as the Data General MCA, but all the computers had to be in one room and it could only handle 16 systems. Metcalfe remembers that the cables were a full 1.5 inches thick.

Metcalfe and other employees used text terminals at their desks. Although these linked to a minicomputer at 300 bps, this was not nearly fast enough to send high-resolution files to a laser printer that could handle one page per second.

They were trying to use old connectivity for a brand new digital world, and although not everyone agreed with him, Metcalfe was convinced that networking was crucial for new computers, as their power would be wasted if they were not connected.

Metcalfe and Boggs imagined a system that would dramatically outperform any other LAN available at the time.

Their aim was to connect 255 PCs up to a mile away from each other, at a few hundred Kb per second. They also wanted to eliminate the rooms full of cables previous networks required.

Metcalfe and Boggs proposed a network that would operate at a speed of 2.94Mbps and meet all the other specifications. That speed would today be referred to as 3Mbps, which is a decent speed on a cellphone with 3G. Metcalfe will however not even now round the number up, as the 60Kbps error that would be introduced was serious bandwidth in 1973.

It was in fact higher than a transcontinental Internet trunk’s speed. If the new speed is however compared to a 300bps desktop connection, the new network was approximately 10,000 times faster.

When they designed the network, distributed computing was emphasized. This new concept was at the heart of all PARC’s work at that time and represented a big shift from the huge, time-sharing and centralized systems that was prevalent in computing since its origin in the 1950s.

All computers on the new Ethernet LAN shared a single cable, with the algorithms running the network distributed between them. An extra board was added to each computer and the microcode for Ethernet was implemented on standard microprocessors.

Metcalfe explained that a single cable ran in the corridor and all PCs would simply be plugged into the cable close to where they were located.

The network was up and running by November 1973. In the beginning, users could order Altos with or without network capabilities, but everyone depended on Ethernet pretty soon. One reason for this was the development of an application that tested the semiconductor memory of an Alto, a technology that had not been proven at the time. Chuck Thacker, a PARC scientist developed the diagnostic tool that ran on Altos and tested their memory while users were not using the machine.

The test results were sent to a separate system via the Ethernet network.

Ethernet was however mainly used to send jobs to printers and connecting Arpanet via a router and long-distance lines. Metcalfe explains that evolution came gradually with laser printers being introduced in 1974, followed by email in 1976.

Although the use of Ethernet expanded in the 1970s, it was limited to Xerox and other institutions where cutting-edge computer research was being done, including MIT and Stanford. Xerox also donated Ethernet and a few Altos to the White House.

Xerox initially intended to sell Ethernet as a standalone product named The Xerox Wire, but in 1980 opted to propose it to the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers as an open standard. At around the same time, other companies had developed their own LAN schemes, bringing numerous options to the industry. Ultimately, the IEEE selected Ethernet, Token Ring by IBM and Token Bus from General Motors as standards.

Although Token Bus did not last long, Token Ring and various other LANs, including ARCnet, survived.

Metcalfe noted that the next few years were spent killing each other, but after a long battle, Ethernet eventually won by the late 80s.

Companies including Digital, Intel and 3Com backed Ethernet. The latter was a small company that Metcalfe had started to serve the emerging market for network gear and adapters.

Although the PARC team took Ethernet up to 20Mbps, the proposed standard was scaled back to 10Mbps to ensure compatibility with Intel’s chips. They were however not sure why anyone would need so much speed. History has now shown that much more is in fact needed.

Metcalfe laughs when he recalls how they argued about whether 10 was too much. This was followed by 100Mb, a gigabit, 10Gb, 40Gb, and 100Gb. 400Gb is now being standardized, while terabit is being discussed.

Just take a look at this 40G media converter to see where it is going now.

He was always surprised to see new applications emerging whenever Ethernet was sped up.

As with most technologies that are widely used, success has led to more success. Each iteration became cheaper as it grew more pervasive. Metcalfe believes that the main key to Ethernet’s success has been that each version is backward compatible with the previous ones.

Metcalfe holds the patent for Ethernet together with Boggs, Butler Lampson and Thacker, while other employees at PARC helped develop hardware and for the network. Metcalfe currently teaches at the University of Texas at Austin and is wrapping up a career at Polaris Partners as a venture capitalist. Boggs was a co-founder of LAN Media, a manufacturer of network adapters. The company was acquired in 2000 by SBE.

Although Ethernet started out on coaxial cable and later migrated to twisted-pair, it has been extended to other media and has formed the basis of other network technologies.

In fact, here in ADnet, we still offer a range of legacy products such as 10Base2, 10Base5, and AUI converters to more traditional 10BaseT. You can check out range of these products here.

Even if 1Tbps was not envisaged by the creators, they did think about different types of Ethernet. In the May 22 1973 memo, Metcalfe mentioned The Ether Network running over phone or cable TV lines, powerlines and radio.

Ethernet was ultimately used in all the other media, including wireless.

According to Metcalfe, it forms part of the basis for Wi-Fi. The technology has evolved into something very different from what Metcalfe and Boggs originally built, and it has had “hundreds of inventors” along the way. That’s why Metcalfe is looking forward to Wednesday’s event.

He explains that when inventors get together, they argue about who was first and who invented what. He does however feel that he is enough to realize how ugly it can get, and that’s why he prefers to stop arguing and simply celebrate everyone’s contributions.